Lemma 7½

For any convex shape \(C\), the diameter of any element of \([C,G]^-\) is \(\text{max}\left(\text{diam}\left(G\right), \text{diam}\left(C\right)\right)\).

proof:

First, if \(\text{diam}\left(C\right) \geq 1\), then \(G\) is accomodated by \(C\), meaning that any element of \([C,G]^-\) is \(C\), and so has a diameter of \(\text{diam}\left(C\right)\). Therefore, assume \(\text{diam}\left(C\right) < 1\)

Let \(c\) and \(g\) be instances of \(C\) and \(G\), and suppose \(\text{diam}([c,g])>1\). Because the convex hull of a shape has the same diameter as the shape itself, there are two points in \(c\cup g\) that lie more than a unit apart. Neither \(c\) nor \(g\) has a diameter above 1, so one of these points must lie outside \(c\), and one lies outside \(p\). Therefore, define \(p_c\in c/g\) and \(p_g\in g/c\), with \(\ell\left\langle p_c,p_g\right\rangle > 1\). There exists a pair of points on \(\left\langle p_c, p_g\right\rangle\) that are a unit apart, one of which is internal to \(c\). By Corrolary 4½.1, \(c\) and \(g\) are not fully intersecting, and so \([c,g]\not\in[C,G]^-\) by Theorem 4.

\(\square\)

This is a milder version of a much more significant theorem that this section has been building to.

Theorem 4¾

For any convex shapes \(C\) and \(D\), the diameter of any element of \([C,D]^-\) is \(\text{max}\left(\text{diam}\left(C\right), \text{diam}\left(D\right)\right)\).

proof:

Without loss of generality, assume \(\text{diam}\left(C\right) \geq \text{diam}\left(D\right)\). To force a contradiction, assume \([c,d]\in[C,D]^-\) where \(\text{diam}\left([c,d]\right) > \text{diam}\left(C\right)\). Additionally, without loss of generality, we may imagine zooming in or out until

$$\text{diam}\left(C\right) = 1 \geq \text{diam}\left(D\right)$$

Next, without loss of generality, imagine rotating and translating \([c,d]\) such that the two points in \(c\) with a distance of 1 unit lie on \(\left(0,0\right)\) and \(\left(1,0\right)\). Define \(c_t\) to be the boundary of \(c\) that lies above the \(x\)-axis, and define \(c_b\) to be the boundary of \(c\) that lies below the \(x\)-axis. Because \(\text{diam}\left([c,d]\right) > 1\), there exists a point on the boundary of \(c/d\), and a point on the boundary of \(d/c\) that are more than a unit apart. Therefore, define \(p_c\in c\) and \(p_d\in d\) to be two points such that

$$\ell\left\langle p_c,p_d\right\rangle >1$$

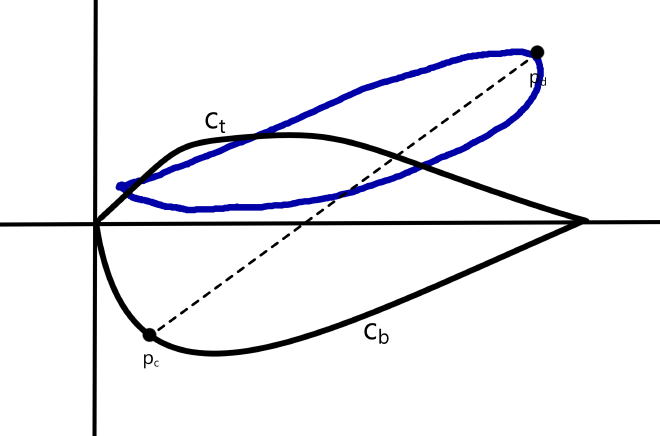

As of right now, \(c\) only has points defined at \(\left(0,0\right)\) and \(\left(1,0\right)\), and so this setup is symmetric around the \(x\)-axis and \(x=0.5\). Therefore, assume without loss of generality that \(p_d\) has a \(y\) coordinate greater than or equal to 0, and a \(x\) coordinate greater than or equal to 0.5. If \(p_c\) lies on \(c_t\), there is a point on \(c_b\) that is even further from \(p_d\), so assume \(p_c\) lies on \(c_b\). In total, the situation looks like this:

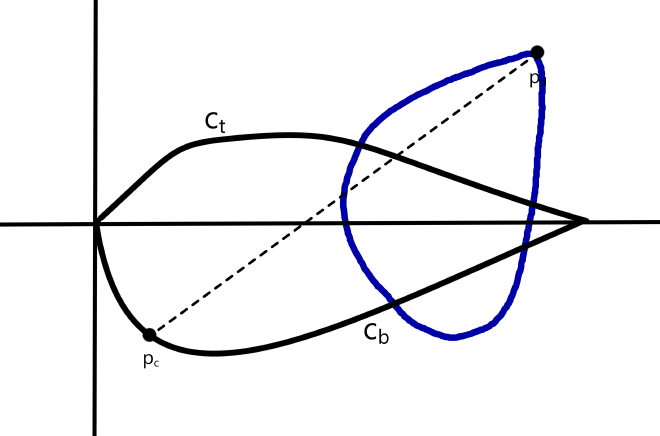

Unfortunately, I don’t think we can make any more assumptions without loss of generality from here. One thing we do know is that \(d\) must be fully intersecting with \(c\), and therefore must “cross” through it. There is therefore a line inside \(d\) that passes from one boundary point of \(c\) to another. This line can either pass from \(c_t\) to \(c_b\), or it doesn’t, in which case the line must pass through \(c_t\) twice. These two possibilities are illustrated below:

| Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|

|  |

For now, let’s assume Case 1, so that there is no line in \(d\) passing through \(c_b\), but there is a line that passes through \(c_t\) twice.

Let \(d_1\) be the point in \(d\) with the lowest \(x\) coordinate, and let \(d_2\) be the point in \(d\) with the greatest \(x\) coordinate.

\(\square\)